The study of the design process and of the mechanisms that designers apply to develop projects and find creative solutions to complex problems is one of the most established areas of design research and at the same time it is also one of the fastest evolving areas, due to the drivers of change brought about by the increasing availability of data collected through digital channels and then used to predict and direct

people behaviour and choices.

The ongoing pandemic has shown us that being able to stay informed, read and interpret data correctly (but also collect it in the right way) can make all the difference. Good use of data has enabled many lives to be saved, and where this has not happened we have seen more emergency situations.

This reveals how the role of data in contemporary society has become one of the most central and debated issues, from the economic and ethical issues that govern its collection, usage and monetisation, to the alternative models of capitalism that are being generated due to its centrality for companies and institutions. This issue is now made even more relevant by the development of a number of technologies centred on the use of data: first and foremost, Artificial Intelligence which, working with large amounts of data, allows us to imagine unprecedented futures.

Currently, there is a wide debate about the implications of this scenario, which has already led many international institutions to make it a leading research topic. The European Commission, for example, is funding innovative research into both the development of new software and applications and the ethical and pragmatic implications for society. Reflecting on the form, nature and value of the data we use and how we use it is, therefore, also central for designers, both in research and in practice, to generate new knowledge about the relationship between analytical-exploratory activity and creative potential.

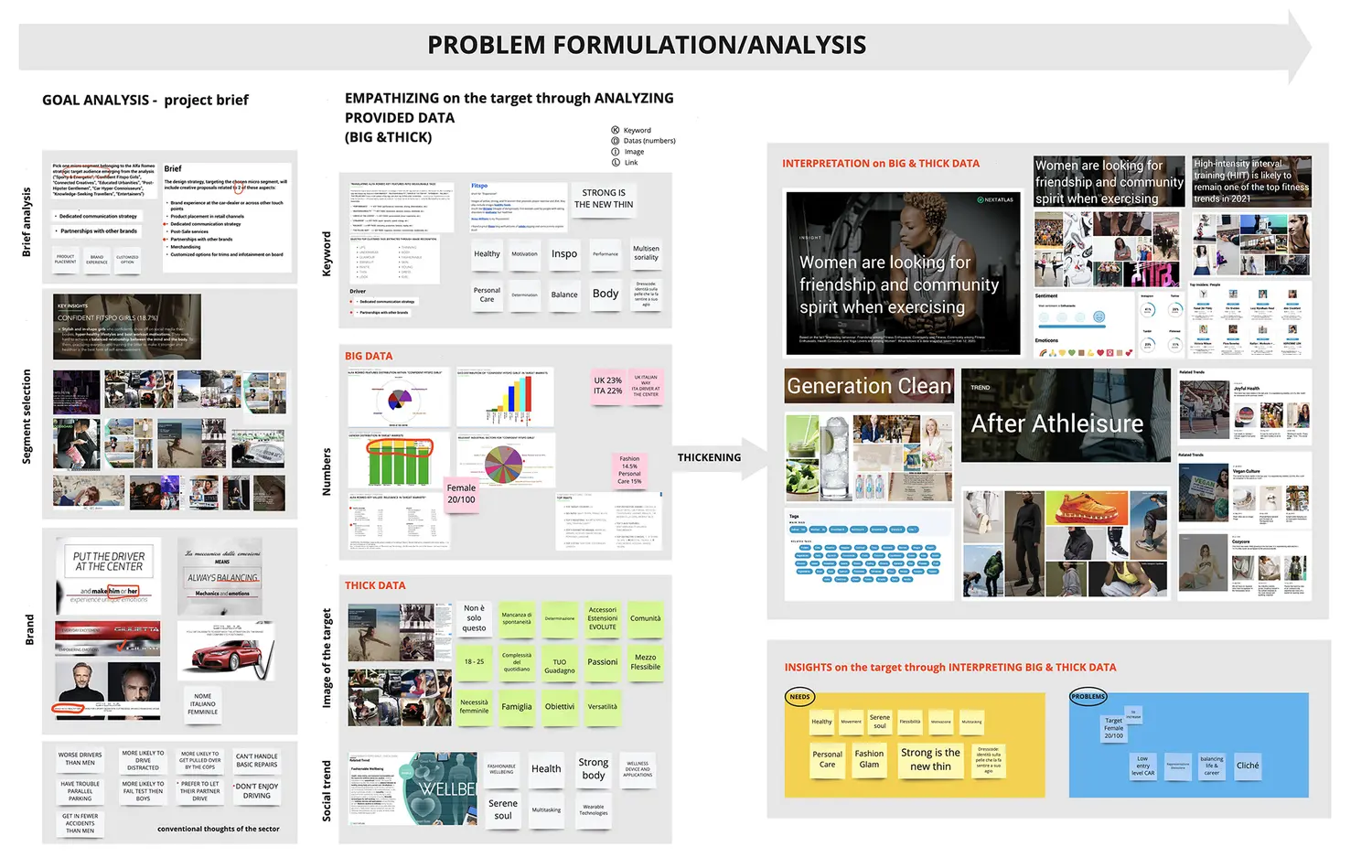

Design has so far paid little attention to what data it has used because it has mainly focused on its ability to empathise with people and to be inclusive. Design is in fact an inclusive discipline able to put people at the centre of innovation processes capable of understanding desires and needs, also through an accurate field study. During this process, the designer collects data both by studying current phenomena, contexts and trends and by using direct observation methods.

This way of studying and understanding a design problem leads designers to collect at least 15 different types of qualitative data ranging from user observations to direct interviews, information provided by the client, and their own personal experience. Such data, which seeks a deep understanding of people, behaviours, contexts and histories, is referred to inethnography as Thick Data, which describes people backgrounds and cannot be quantified; for creatives, this type of information is the main source of inspiration.

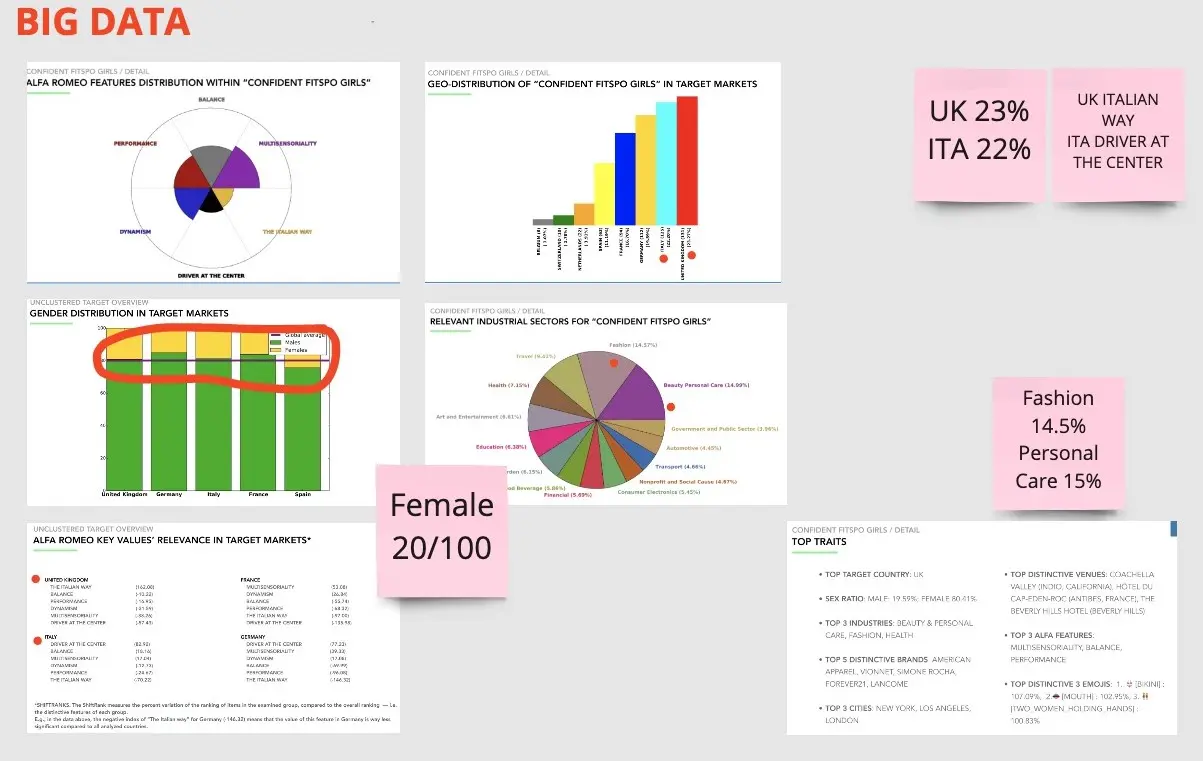

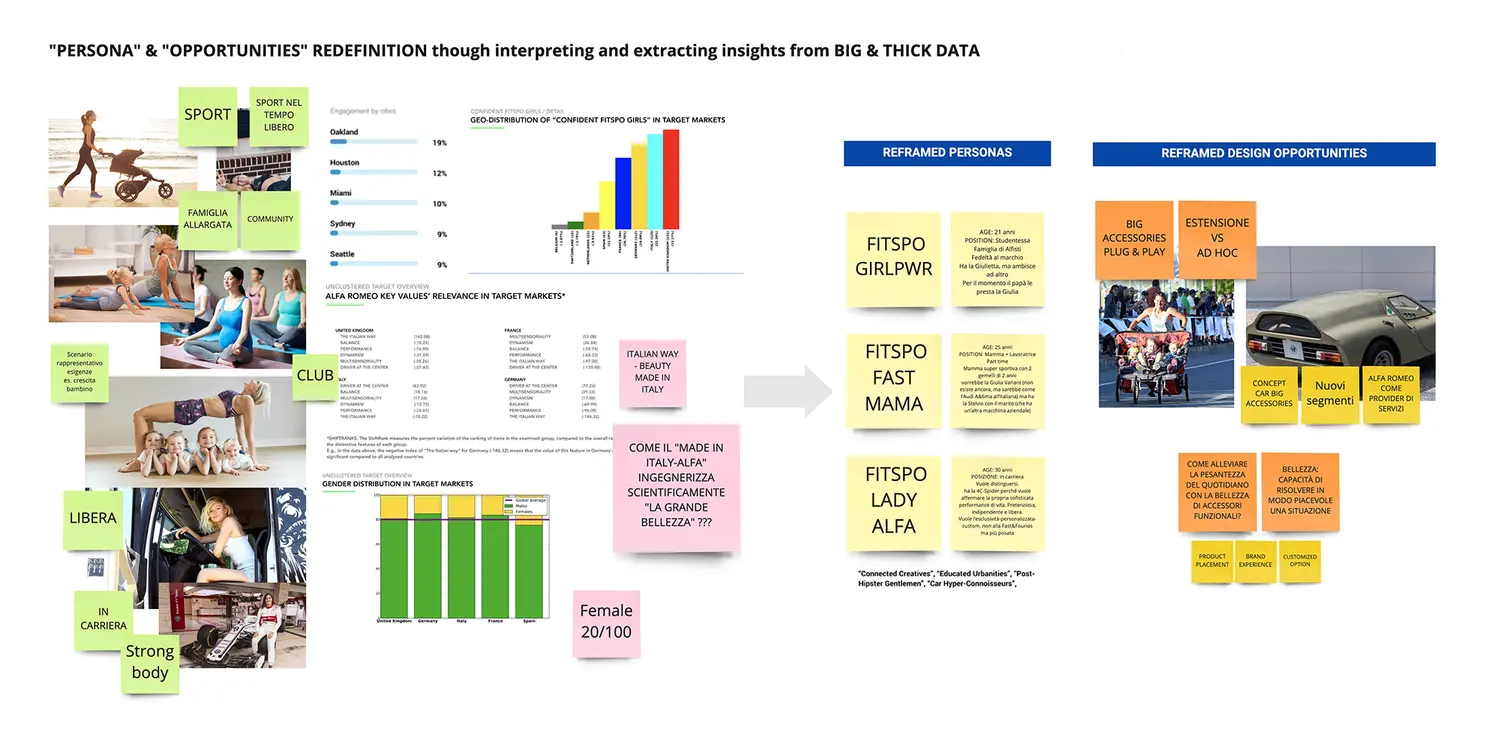

But what happens to the design process when we combine this thick, meaningful data with the possibilities offered by another type of data with opposite characteristics, namely Big Data, which is numerical, cold and potentially able to provide a panoramic view of society behaviour?

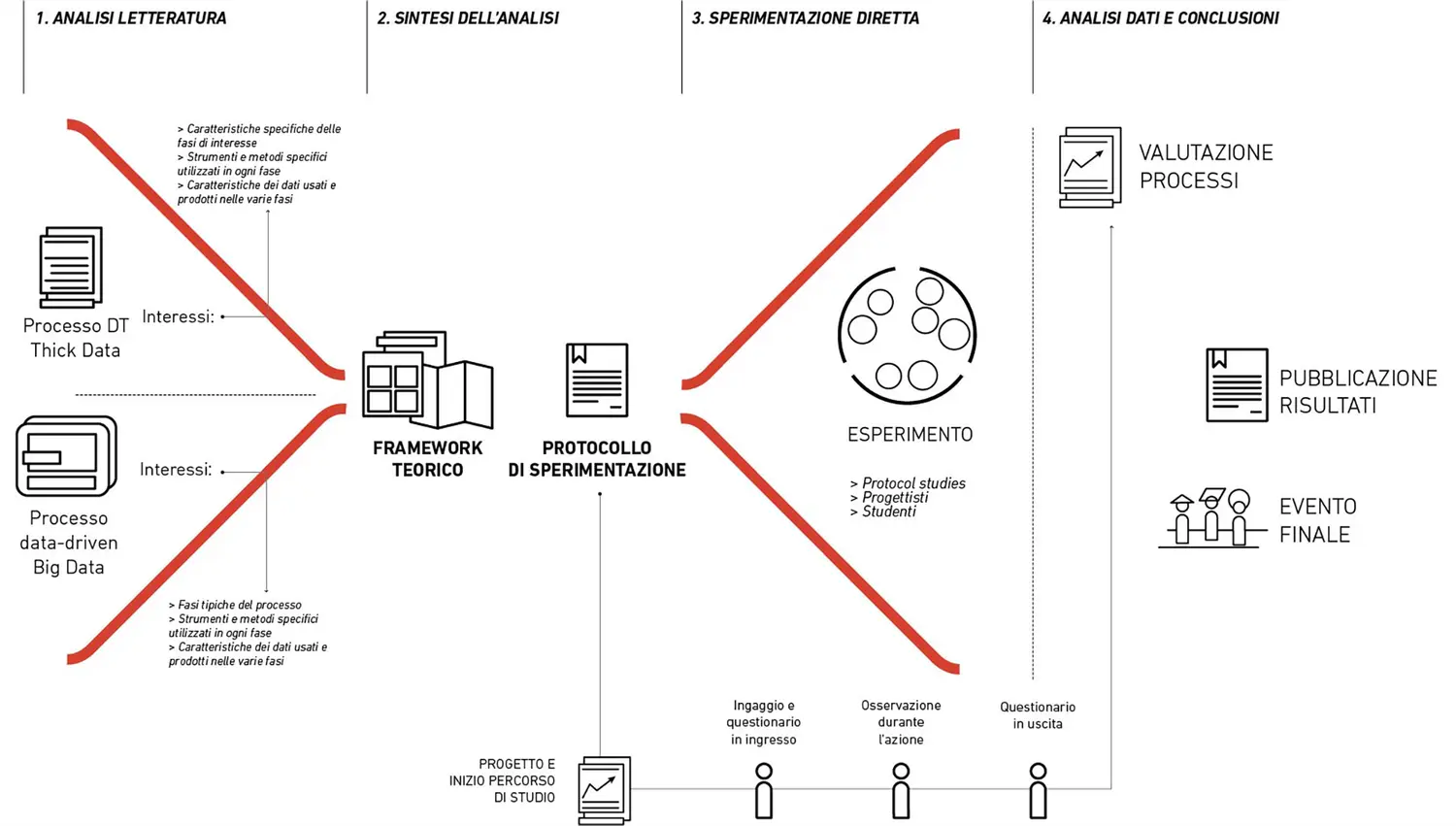

In order to answer this question, DesAI has set up a three-stage research project:

- Mapping of the conceptual landscape, with the aim of synthesising the conceptual model of reference, mapping and cataloguing the characteristics of thick data and big data through literature synthesis and investigation of the characteristics of the data used in the different phases of the design process.

- Collection and analysis of case studies, with the aim of analysing the use of mixed data types in the design

process. - Experimentation and direct observation, with the aim of simulating a design process by observing "in the laboratory", i.e. in a controlled context, the use of mixed datasets.